How to Write Short Poems

So, you want to learn how to write short poems because you think that short poems are easy. They can be easy --- or easier --- if you choose to write in one of the short-form poems. With these formats, at very least, you have a template. A template supplies the form, the rhythm, and when appropriate, the place for rhyme. While that might seem more complicated, it is in fact a road map to success.

Let’s start with some of the short-form poems: haiku, diamante, and limericks. Then we can move on to couplets, as the shortest couplet would consist of two rhyming lines. Now that’s short!

How to Write Short Poems: Haiku

Haiku is a short poetry form originating from Japan. While the language is very different from English, the form translates well. A well-written Haiku has a certain tone. The last line is often abrupt, and when done well, present the reader with a surprise. The basic rules or format of Haiku (link) I three lines of 5 – 7, and then another of 5 syllables in each line.

Here is a sample Haiku from a page of Haiku examples (link).

Clean Brisk day. The clouds

High in the sky. And then a

Crackling brown leaf falls.

For more instruction on how to write this short poem, go to How to Write a Haiku.

How to Write Short Poems: Limericks

Limericks are short, light-hearted poems that are funny – or at least mildly amusing. The Limerick ahs five lines in the AABBA rhyme scheme. The first two lines and the last line line are longer than the third and fourth lines, creating an expectant rhythm, making the last rhyming line satisfying to the ear. Then there is the matter of syllables. The first two and last line are longer than the middle two rhyming lines. It’s hard to establish an exact syllable count for each. However, the longer (1st, 2nd, and 3rd lines) are 7 to 9 syllables, and the 3rd and 4th lines are generally 5 syllables. Let’s read the following examples to get a true picture of the form of the Limerick.

Edward Lear is the standard bearer of the Limerick. He was born near London, England in 1812. He was an artist and illustrator and became well known for his nonsense verse and illustrations.

The first example of a limerick is by Edward Lear.

There was an old man with a beard

Who said, “It is just as I feared.

Two owls and a hen

Four larks and a wren

Have all built their nest in my beard.

Here is a second example from my own page of Limericks.

There was a young man from Grand Blanc

Who decided to act on a prank.

He pulled out a skunk

from the back of his trunk

and that’s why he stunk and he stank.

To get started writing your own limerick, start by choosing a topic – usually an unusual person or character. Make certain that your lines end with easily rhyming words. Keep in mind that even Edward Lear, the most famous of all limerick-writer, used the same end rhyme (beard) in the first and last line of his classic limerick, above. Feel free to use this technique, but only if it works! That means that the rhythm is on-pitch and the last word and the last line makes sense – and with some luck makes you and your reader smile.

Give limericks a try! Once you get the hang of it, they are fun and possibly addictive.

How to Write Short Poems: Diamantes

Diamantes are rigidly proscribed and therefor (in my opinion) less inspired. That said, they are perfect for the classroom, as they are similar to a paint-by-number piece of art. It can be an entertaining exercise that results in – voila! –a short poem.

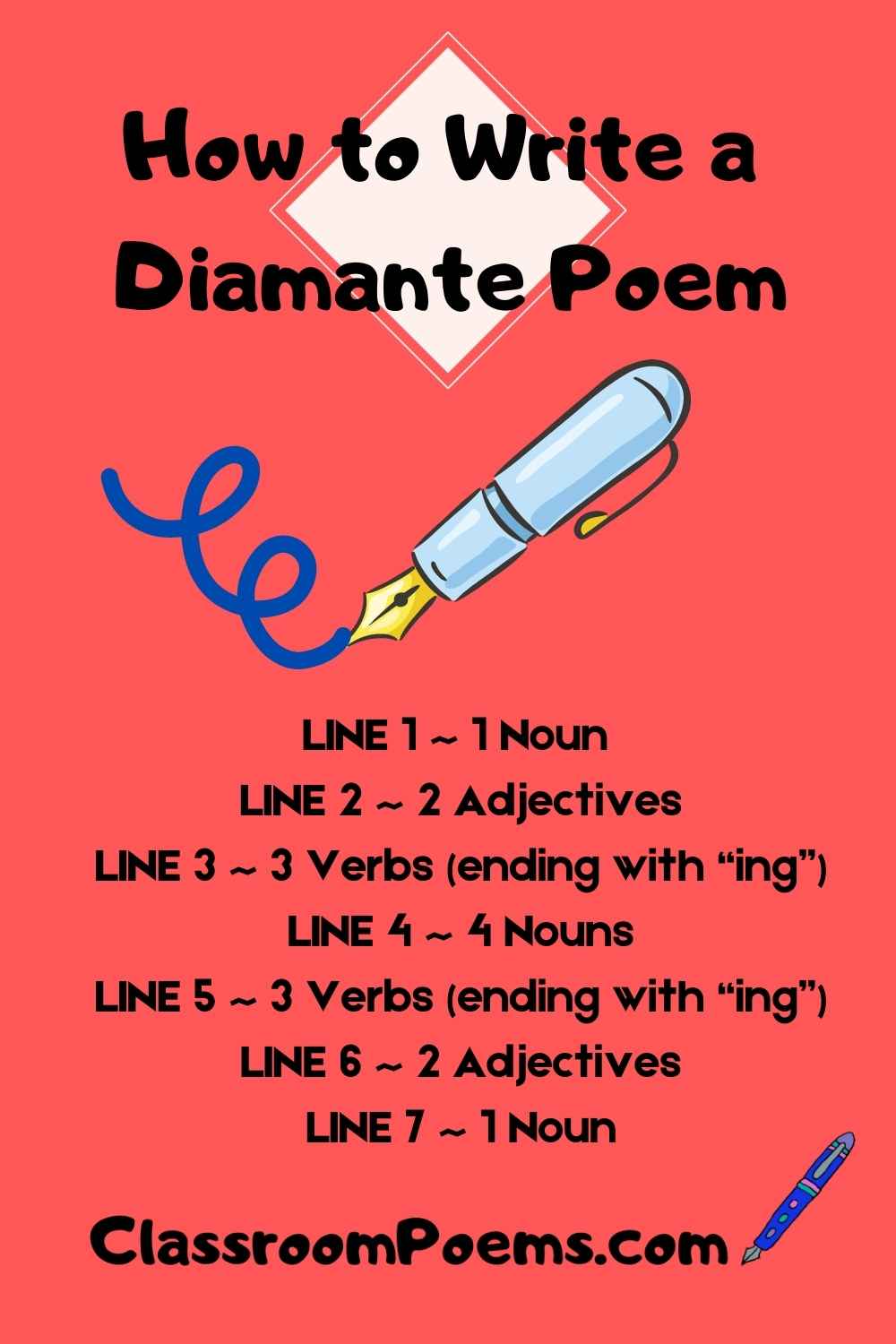

Here is the format. This poem is called a diamante because tis’ written or printed form resembles a diamond shape. Here is a link to “How to write a Diamante.”

Line 1 – 1 noun

Line 2 – 2 adjectives

Line 3 – 3 verbs ending in “ing”

Line 4 – 4 nouns

Line 5 – 3 more verbs ending in "ing”

Line 6 -2 adjectives

Line 7 – 1 noun

You can write a diamante on one topic – or make a switch to a second topic at line 4, by making the first two nouns about the first topic and the second two nouns about the second topic.

Here is an example of a single-topic diamante.

Lamp

Asian, beaded

lighting, shining, flashing

cord, electric, shade, base

glowing, illuminating, glittering

colorful, shapely

Lamp

Here is an example of a two-topic diamante. Notice how the change comes about

in line 4, where the first two nouns are about the first topic, and the second

two about the second topic.

Nuts

crunchy, salty

crunching, chewing, crackling,

macadamia, walnut, tomato, cucumber

refreshing, chopping, tossing,

crispy, crunchy

Salad

The diamante is more about puzzle cracking than about writing an inspired poem. But they are great addition to a classroom lesson and will help some students write a successful poem.

How to Write a Short Poem:

The Couplet

Couplets are two lines of rhyming verse. A poem can be as short as two lines, or as long as it needs to be, according to the poet. But you came here to learn about how to write short poems. Couplets are a little tricky because while they are not free verse LINK (with no rules and even no need to rhyme), you are on your own to develop rhythm, as well as rhyme – and also for the poem to make sense and feel complete.

Here are two of my own short couplets.

"Oh my!" the portly gent called out. "I cannot find my hair.

I washed and put it out to dry, and now it isn't there!"

And the second short couplet:

When Silly Sally irons her clothes, they come out looking awful.

She did not read the label and her iron was meant to waffle.

These are short, but they are more challenging. Give them a try and if you like what you’ve written, whether a haiku, a limerick, a diamante, or a couplet, please share them on our publishing poetry page.